On November 8th, 2002, Universal Pictures released the Curtis Hanson-directed film 8 Mile. Scott Silver wrote the original screenplay. Filming began in September, 2001 in various Detroit, MI suburbs and ended in January 2002.

As an avid wearer of Carhartt products over the years, I have been taking notice of Carhartt styles used for characters’ wardrobes in movies and television productions. When time allows, I assemble the information into a post such as this for the series, “Carhartt in the Movies and TV.”

8 Mile was a memorable movie for many reasons, notably for being the only lead role in a major motion picture by Eminem.

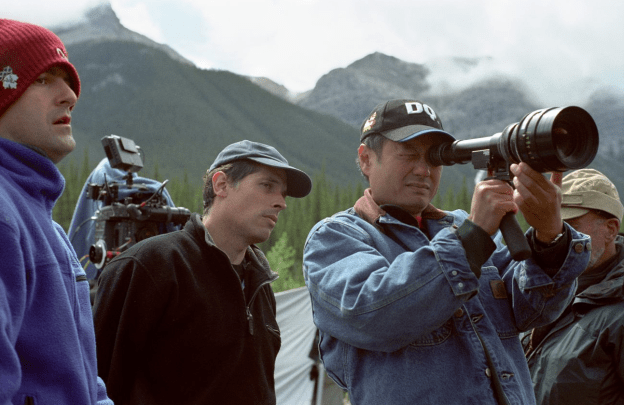

I spotted one Carhartt product in the film, worn by one of the supporting characters, Cheddar Bob, and played by actor Evan Jones. Jones was fitted with a less well-known Carhartt coat that has since disappeared from the production line not long after the release of the film.

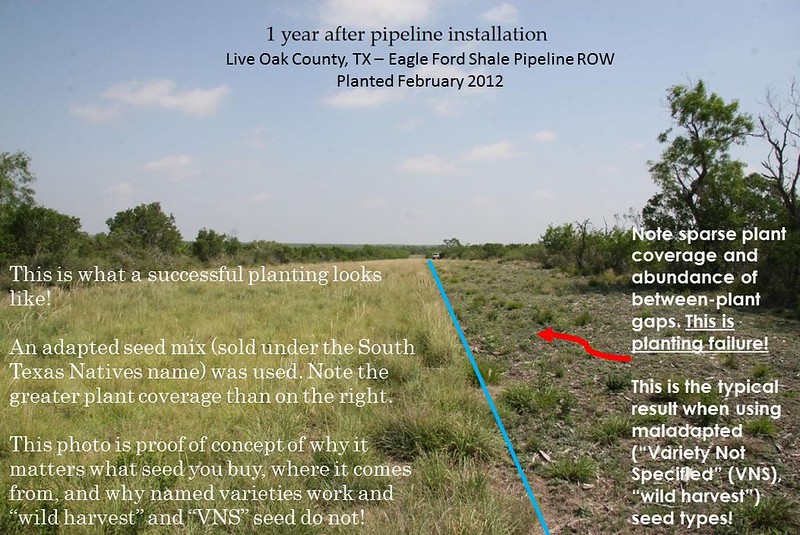

Cheddar Bob (second from left) and the crew. Image presumably from a DVD capture or higher quality source. Original source unknown. Thanks, internet search results.

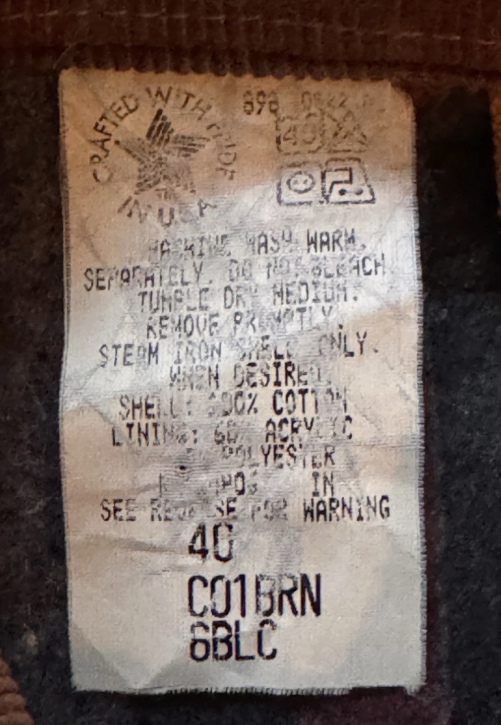

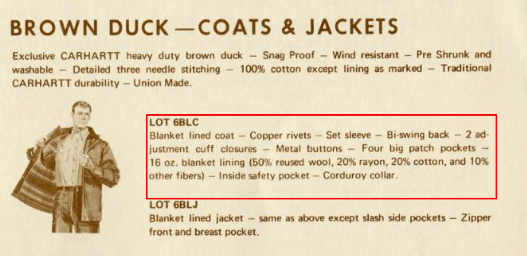

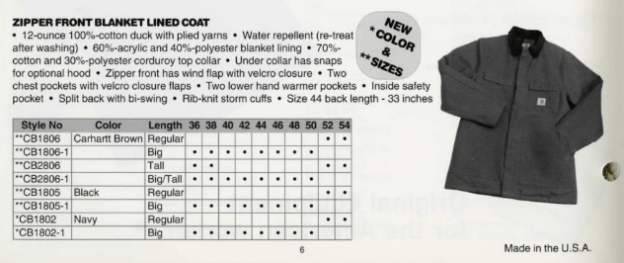

Specifically, Jones wore the Brown Duck Zipper Front Blanket Lined Coat (CB1806). The lot number (commonly referred to as the “style code”) was color- and style-specific. From 1995 to 1998 customers could order a “CB1806” and receive exactly that. The tall sized variant in the Brown Duck color option was CB2806. The Zipper Front Blanket Lined Coat was also produced in “Black” (CB1805) and “Navy” (CB1802).

Lot number CB1806 is somewhat intuitive compared to today’s 6-digit style numbers. We can “read” the lot number as follows:

C – Coat.

B – Blanket lined.

1 – Presumably indicates the first production of the style.

8 – “8” indicates a regular size, as the tall size contains the number “9” in the style code (i.e., CB1906).

0 – Possibly indicated the sequence in a series of production or some arbitrary designation.

“6” – The old color code for “Brown Duck.”

Screenshot from 1996 catalog entry for the CB1806. This catalog entry contains one of the earliest examples of the color, “Carhartt Brown,” which was the updated color name for “Brown Duck”.

Carhartt made clear distinction between coats and jackets, even if the general public uses the terms interchangeably (and often technically incorrectly).

The story in the film is set in 1995. Jones’s coat is contemporary to the time of the story and to the time of filming. The coat style was first produced in 1994, released in 1995, and discontinued in 2003-2004.

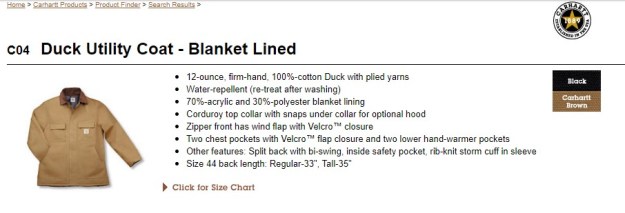

Beginning in 1997, Carhartt started consolidating their lot numbers into style codes. The CB1806 became the C04, signifying it was the fourth coat produced by Carhartt under the simplified style code system. The old color code “6” for “Brown Duck” became “BRN” for “Carhartt Brown,” and the style name was changed to “Duck Utility Coat.”

Screenshot from the Wayback Machine on the Internet Archive. Circa 2003.

It is possible Jones wore the C04. Without seeing the style tag and with no changes to the style from CB1806 to C04, the two “styles” are indistinguishable based on outward appearance.

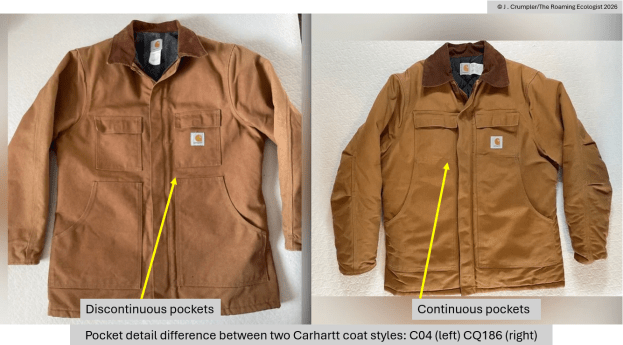

The Duck Utility Coat was one of only two coat styles Carhartt produced with a blanket-lining and a zipper front. All other blanket-lined coat styles produced in this era had traditional 5-button fronts. Based on overall outward appearance, the Duck Utility Coat more closely resembles the Arctic Traditional Coat. The key distinction between those styles is the discontinuation of the pocket layout on the Duck Utility Coat shown below.

With simplified style codes came simplified style names. Metaphorically, that change also signaled the beginning of the end of “brown duck” as common workwear. Workwear today is mostly cheap petroleum products bordering on fast fashion trash and accompanied by intrusive advertising. This change in workwear can also signify the change in labor–it isn’t as physical as it was and the future of labor remains murky.